Good Question! FAQs

Readers ask really good questions! Click on them for the answers.

Q. How do you get the plasticine into the books?

Ian Crysler, camera ready!

A. My husband, Ian Crysler, is a professional photographer and he shoots all my work. Ian lights each picture to look its best. Lighting can create special effects, like the night time look of Tunnel’s End in The Subway Mouse, or the shadow of the elephants foot in Effie. Other effects can be added later on the computer, such as the glowing candles in The Night Before Christmas. The digital photos are sent to the book publisher, where the art director adds the text (words). From there, the files are sent electronically to a printing house where the words and pictures are printed onto paper and bound into books.

Press approval

I visited the printing company Friesens in Altona, Manitoba for the press approval of Perfect Snow. At a press approval, large proof sheets of each part of the book and cover are printed and carefully checked to make sure everything looks just right. Any necessary changes are made, and the book is printed. It was exciting to tour the factory and see thousands of books in all stages of production, and especially to see pages of Perfect Snow coming off the press to make a stack- like a perfect snow drift!

Q. How did you start working with plasticine?

Barb meets A. J. Casson

A. I played with plasticine a lot as a kid. While studying illustration at the Ontario College of Art and Design I experimented with plasticine to make a dimensional picture for a class project. The project was a surprise success-everybody laughed! When I entered another plasticine picture in a calendar contest I was embarrassed to find out that one of the judges was the famous painter and Group of Seven member A.J. Casson. To my surprise and relief, he laughed! I won the contest. After that, I decided to take having fun more seriously, and include plasticine artwork in my portfolio.

A. Plasticine was invented in England over one hundred years ago, by art teacher William Harbutt. He had been searching for an easy to use modelling material for his students and the final product was the result of many experiments. Not only did the adult artists fall in love with “the clay that never dries out”, so did William’s six children. They filled the house with plasticine castles, model boats, battle scenes and fountains.

William first thought of his invention as a teaching aid, but when he saw the delight it brought his family he decided to package it for sale, so other children could enjoy it. The whole family helped come up with the name Plasticine.

Since then, millions of pounds of Plasticine have been shaped by artists, architects, engineers and children into everything from military maps in both World Wars to models for the first space suit, from aircraft design to dental models and dinosaurs.

An early pamphlet for Harbutt’s Plasticine declared “There are 101 uses for Plasticine”. Albert Blanchard, chief British military modeller in World War I, valued most of all the amusement and education that plasticine brought to children. He said: “You can teach art and geography with it. You can demonstrate carpentry and plumbing. You can roll it, cut it, mold and shape it, and then crush up what you have made and start all over again. No wonder it fascinates people so much that after playing with it as children, they keep the habit for the rest of their lives.” I couldn’t agree more!

Q. What do you do with your pictures after they have been photographed?

A. Plasticine art can be framed in a shadow box and hung on the wall. I keep a few framed pieces, some go to family, friends or the author of the book, and some are sold or donated to collections and galleries. For example, all the pictures from Read Me a Book were donated to the Toronto Public Library Foundation and are displayed in various branches throughout Toronto. The Osborne Collection at the Toronto Public Library has an outstanding collection of original Canadian picture book art including work by Brenda Clark, Marie-Louise Gay, Michael Martchenko – and me!

A. Plasticine art can be framed in a shadow box and hung on the wall. I keep a few framed pieces, some go to family, friends or the author of the book, and some are sold or donated to collections and galleries. For example, all the pictures from Read Me a Book were donated to the Toronto Public Library Foundation and are displayed in various branches throughout Toronto. The Osborne Collection at the Toronto Public Library has an outstanding collection of original Canadian picture book art including work by Brenda Clark, Marie-Louise Gay, Michael Martchenko – and me!

Q. What comes first, the words or the pictures?

Manuscripts for The Subway Mouse

A. The words come first when I illustrate a book written by someone else (like Gifts by Jo Ellen Bogart, or Peg and the Yeti, by Kenneth Oppel). The author writes a story (manuscript), and sends it to a publisher. If the story is accepted, the publisher then looks for an illustrator that is a good match. If the illustrator is me, I read the manuscript (many times!) and start to imagine the pictures that will end up in the book. Sometimes I am both the author and illustrator of a book (like The Party or The Subway Mouse). Because a picture book is a story told in both words and pictures, and I THINK in both words and pictures, I usually imagine them both right from the start. I fill pages with notes and doodles. Both words and pictures go through a lot of changes and improvements before they are finished.

Q. How do you make your pictures look so real?

Model for Fox Walked Alone

A. I collect research. For some books, that just means looking at things and doing a quick sketch, or taking photos. Some of the trees in Picture a Tree are favourite trees I remember from when I was small and some are trees I took pictures of while walking our dog Ruby. For Peg and the Yeti, I found lots of pictures and books about Mount Everest so that the scenery would look right. For the The Subway Mouse, Ian helped me take pictures in subway stations around the city. I also collected lots of candy wrappers and bought real feathers for some of the effects in the book.

Reference books

I have a library of reference books in my studio, and I look things up on my computer. I also have a collection of plastic model animals to draw from. Sometimes I ask family or friends to pose. Our daughters Zoe and Tara were the models for The Party.

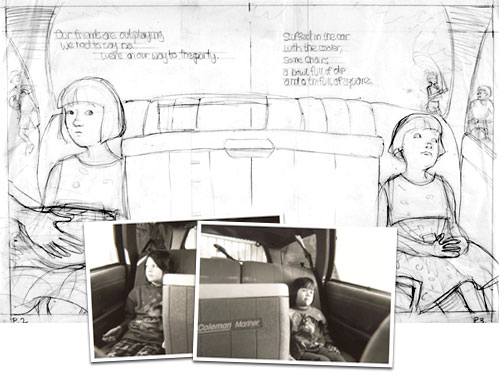

Zoe and Tara pose for The Party

Q. How do you decide what pictures to make?

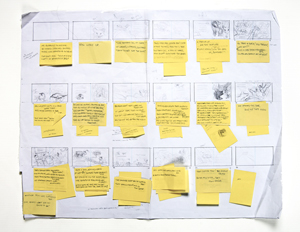

Storyboard for Fox Walked Alone

A. I get to know the story inside out, and then start sketching to get a feel for the characters and setting. Next, I make a storyboard. Storyboards are big pieces of paper divided into small squares to represent all the pages in the book. I can make small thumbnail sketches to map out the story in the squares. I decide how to divide the words up to match the pictures, and which pictures should be big or small, close up or far away. It’s a little like making a movie, choosing scenes and keeping the action going so that the reader wants to turn the page.

The next step is to make the full sized rough drawings. There is a lot of working and reworking before the roughs are final. I show the roughs to the Art Director and Editor of the publishing company. Sometimes there are changes.

It is important to listen to suggestions and be willing to work a little more to make your artwork the best it can be. Often a fresh set of eyes can spot a problem or mistake that you have missed. After everyone agrees with the sketches, I get out the plasticine and the real fun begins.

- Drawing for Picture a Tree

- Finished art

Q. Do you sometimes give up on a picture or an idea?

Take a break when you are stuck!

A. Sometimes a story or a picture has a problem that is hard to solve, and I get stuck. It’s a good idea to take a break when that happens, and put it away for a day or two. When I go back to the project with fresh eyes, the solution is usually easy to see.

Drawing by fellow plasticine artist

A. Yes! By the time I finish making a whole book my thumbs are toughened up, but the first couple of days are hard. I guess sometimes it’s true when they say artists suffer for their work…

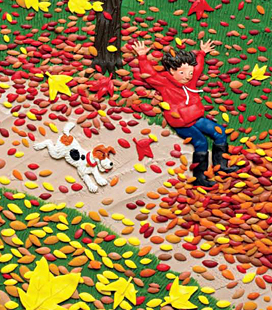

Q. How long does it take to make a picture?

A busy scene from The Night Before Christmas

A. Building a the plasticine picture can take from one to nine days, depending on the size of the picture, and how detailed it is. This scene from The Night Before Christmas took seven days.

Q. How long does it take to make a whole book?

A. Writing the story takes a couple of months, but that’s not counting all the time that I have been thinking about it and making notes. Most of my stories run around in my head for several years before I write them down. It takes about eight months to make the pictures, from rough drawings to finished and photographed artwork.

Q. Why did you add drawings to Perfect Snow?

A. Adding cartoon like drawings in Perfect Snow made it easy to show a lot of information about the characters, and pack in more action. For example, the opening drawings wordlessly set the scene for the book. Frame by frame we see the snowfall that “came in the night”. Also, I LOVE to draw, so it was treat to include drawings in a book. The drawings were made with markers and watercolour wash.

Drawing from Perfect Snow

Is the marble real?

A. Good spotting, it is a real marble! I used many found objects to give The Subway Mouse the look and feel of the real life subway. Some examples: the feathers are real; the candy wrappers are photocopied from real wrappers; the mouse whiskers are snipped paintbrush bristles; the rose that Nib uses as a pillow is a dried corsage. Combining different materials in this way is called collage.

A. Most of my illustrations are made the same size as you see in the books. For some of the very detailed pictures I work a little larger and the art is reduced when it is printed.

Q. How do you get your whites so white?

Clean hands mean clean plasticine

A. Light colours of plasticine, like white and yellow, can easily get dirty after handling dark colours like black or purple. I wipe my hands with a cloth or dry paper towel before switching to a light colour. Kneading a piece of white plasticine for a few minutes also helps remove the darker clay. I store colours separately so the reds don’t get stuck to the blues. Clean hands will help you make the whitest clouds, cleanest snow and the sunniest yellow sun.

Q. Ben from Manitoba: What kind of tree would you be?

A.I love the changing seasons and my roots are in Canada, so I would be happy as a Maple or Jack Pine. But I secretly dream of being a Beech, as described by Lucy in Prince Caspian: “Ah! – She would be the best of all. She would be a gracious goddess, smooth and stately, the lady of the wood.”

A.I love the changing seasons and my roots are in Canada, so I would be happy as a Maple or Jack Pine. But I secretly dream of being a Beech, as described by Lucy in Prince Caspian: “Ah! – She would be the best of all. She would be a gracious goddess, smooth and stately, the lady of the wood.”

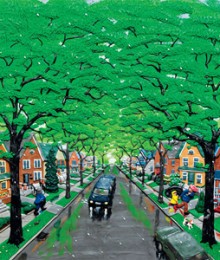

Q. What is your favourite colour?

A. Green. Then all the others.

All my favourite colours

Ruby the dog in Picture a Tree

A. In the past we have had a couple of hamsters, some fish, and for 15 years we lived with a VERY playful wirehaired fox terrier named Ruby. She was white, with brown ears and black spots. I dedicated Picture a Tree to Ruby because the book was inspired by our daily walks in the Don Valley in Toronto. You can Find Ruby on many pages in the book, and also spot her in The Golden Goose and Read Me a Book.

Q. What are you working on now?

Starting something new!

A. I am working on a new picture book! It will be called Story Hunter. It is about a stone age child’s first experience seeing and creating artwork deep in a cave. It will be published by Scholastic Canada. Look for it in 2026!

Q. What advice do you have for aspiring writers and illustrators?

Artists need to spend some time alone, doing nothing in particular

A. For writers: read, read, read and write. For illustrators: look, look, look and draw, read, and then draw some more. For both, the first draft or sketch is just the start. Be prepared to re-do and polish your work until it really is the best you can make it. Keep your best work, and don’t forget to sign and date it! It will be a great record of you progress and development. For all artists, it is very important to spend time alone, not doing anything in particular.

If you are interested in learning about how to have your work published, these organizations can be very helpful:

The Canadian Children’s Book Centre A not-for-profit organization that promotes and supports reading, writing and illustration for young readers. The Centre produces the very useful: Get published! The Writing for Children Kit.

CANSCAIP ( the Canadian Society of Children’s Authors, Illustrators and Perfomers) A national organization with monthly meetings and an annual full day workshop conference “Packaging Your Imagination” in held in Toronto.

SCBWI is an international organization for professional organization for authors and illustrators of books for children and young adults that offers a wealth of resources.

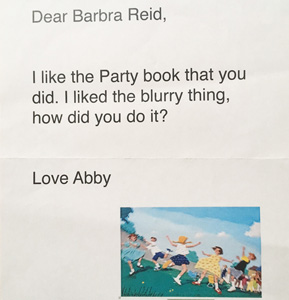

Q. Abby, grade two: How did you make the picture blurry in The Party?

Good question from Abby

A. Good spotting Abby! In this scene, the kids at the party are “spinning in circles until we get dizzy”. First, I set the scene on an angle to make it look tippy. Next, when we photographed the plasticine artwork, I jiggled the picture just as the camera clicked. That made the photo come out blurry. I hoped those effects would make readers feel dizzy too. Did it work for you?

Orange cat spotted in The Subway Mouse

A. Yes! I imagined that the cat in the carrier is the same one at Tunnel’s End. I included a sneak peek for clever readers. Nib also has an image of a cat on the wall of his nest. It’s an illustration of the Cheshire Cat by John Tenniel from Alice in Wonderland. Nib doesn’t know about cats until he gets outside; he was probably curious about the picture when he found it. The outside world is dangerous for mice, but I like to think that all the beautiful and good things make it a good place to live for Nib and Lola and their new family. Excellent observation Amelia!A.